Among some refugee populations, a girl’s first period means she’s ready to marry

26 March 2024

26 March 2024

Born and raised in Kabul, South Sudan, 45-year-old Athou Dak was 14 when she got her menstrual period. For her and many girls her age, this transition meant a lot more than just the near end of puberty. In her culture, the start of a girl's period means that she is ready to marry.

“When I saw blood and told my mother, she shrieked with excitement, attracting the attention of my father and the rest of the community. My father then slaughtered a goat for the clan to celebrate, and they hung a flag on a pole in front of our house.” This flag is often white with a bull painted over it to represent livestock as bride price. It signals to boys and their families the presence of a potential bride in that home. The younger the girl, the more dowry, often in the form of livestock or money, her family shall collect.

At 14, Dak was married off and had five children. The war would later force them out of their country and home, to Uganda. Her husband and one child died here a couple of years ago, leaving just her and her four children. Her eldest daughter is now married too. She got married at 15 years old, also shortly after her period came. However, the events leading to her marriage differ from those that led to Dak’s. “She got pregnant, and went to stay with the boy.” While a few families still practice the culture by which Dak was married, others simply send pregnant teenagers to their “husband” (the boy responsible)’s home, and never look back. In essence, the girl is now married. While such old social and cultural norms are the source of these practices, the disproportionate poverty of refugees has become yet another reason for their continuance.

Where poverty and societal norms intersect

Jane Abangi’s family moved to Uganda from Juba, South Sudan, escaping war. In the camp, her father married another wife and left. Abangi’s mother later contracted HIV in the camp; depressed, she turned to alcohol. “She sent us to live with my aunt because she couldn’t take care of us anymore,” she says. The now 25 year old mother of one was then in school. But her aunt who already had her own kids started to neglect providing for her needs, including sanitary towels for her menstrual period. “We wanted Always (sanitary pads), but she’s not providing. We wanted soap to wash school uniforms, she’s not providing.” Desperate and frustrated, Abangi decided to marry her boyfriend. She was 16 years old. When Abangi has conceived in 2021, her husband passed on shortly after. “I returned to my mother’s house to be taken care of better.” Her mother was barely getting by, and her community was not offering much support. “Even my father-in-law who was still helping died four months later.” Abangi began to sell foodstuffs in the market to sustain her small family.

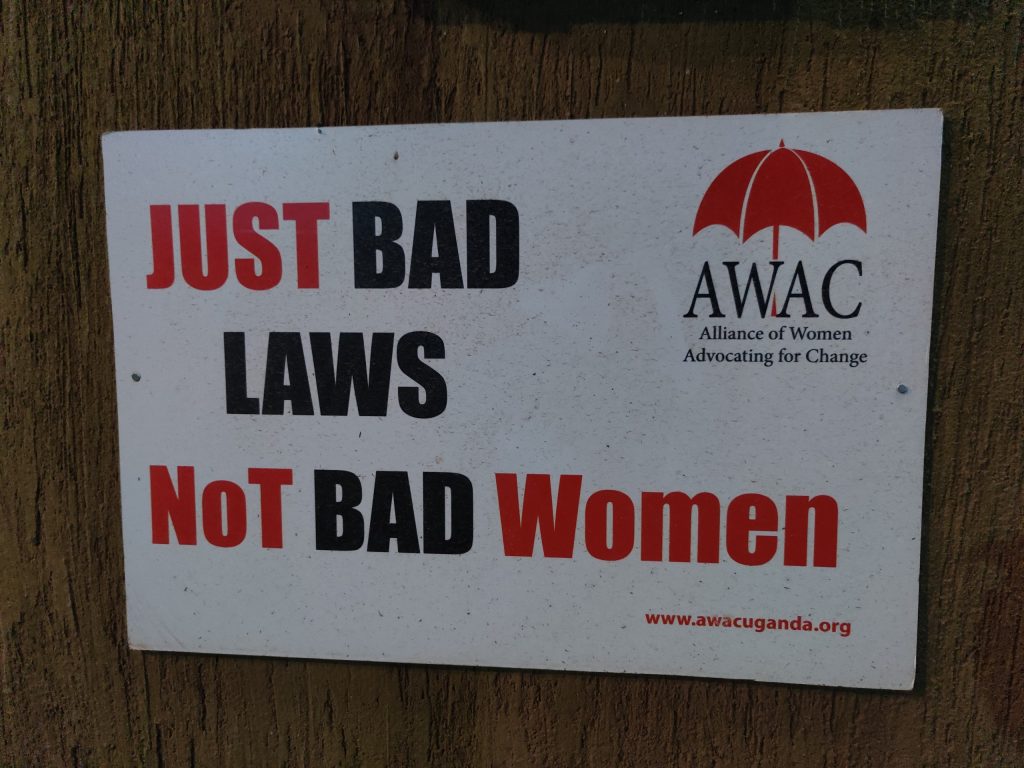

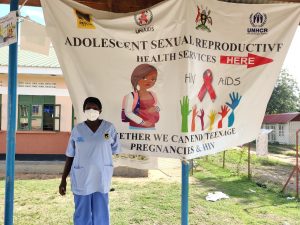

When we meet, she and other girls gather under a brick shelter in Ofua 1, one of the settlement’s zones in the West Nile Region district of Madi-Okollo. They have been convened by the Alliance of Women Advocating for Change (AWAC), under Make Way, an advocacy programme which aims to break down barriers to sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR). “When we are in a group like this, I feel good. I interact with my friends and they also give me advice.” In these gatherings, Abangi and others learn about SRHR and the intersections of their own experiences with reproductive health. In this particular one, a facilitator is making an interactive presentation about SRHR and climate change.

Abangi wants Make Way to bring these sensitization campaigns to parents and elders. “Let them come and teach these things to our parents so that they know that family planning is good, not bad.” Among these communities, contraceptive methods are often frowned upon – with young girls especially being cautioned against it with myths, and those seeking it chastised. Any talk about sex is a taboo in these cultures, and married women are expected to embrace their role of childbirth unquestioningly.

19-year-old Asianzu Teopista intimates that any time people see a girl near the family planning clinic, the gossip and name-calling ensues. Her friend had a contraceptive implant inserted, and has since been subject to name-calling. “Some people are saying that she won’t be able to give birth after 5 years,” Teopista adds. In Family Planning: A Global Handbook for Providers, a publication by the World Health Organisation (WHO) it states that while a woman may experience side effects like irregular menstrual bleeding, contraceptives “do not make women infertile.” In fact, if a woman stops taking contraceptives, even if she has been taking them for a while, she will not be protected from getting pregnant.

Policy barriers to abortion, dire consequences

The Ugandan constitution places stringent restrictions on abortion. As such, health workers can be hesitant, even adamant when requested for the service. As Abangi adds: “If you want to remove the pregnancy, those people at the (health) facility will not help you. You see how young you are and you have messed up. Sometimes you can end up wanting to kill yourself.” In consequence, the adolescents in this refugee settlement have taken up unsafe abortion methods. The Make Way programme is countering this through interventions like fostering youth SRHR sensitisation and empowerment groups in the camp.

The legal age of consent to marriage is 18 in Uganda. The Government Head at Rhino Camp Settlement stresses that it applies to refugee communities, and supersedes even the laws of their country of origin, but adds: “Some families know this, so they conduct the early marriages back in across the borders right before they get here. By the time they arrive, the children are already husband and wife.” – Armitage Basikana, Settlement Commandant. Other families just hide young, pregnant brides inside their homesteads and keep them from accessing antenatal services, to avoid detection. Basikana says that once dowry has exchanged hands, it is difficult to reverse the marriage.

Girls like Dak’s daughter and Abangi often grapple with multiple challenges. From refugee status to poverty, HIV status, single motherhood, illiteracy, and an overwhelming amount of emotional and psychological trauma, early marriages and pregnancies are just the tip of the iceberg. These, coupled with repressive cultural norms, make accessing sexual reproductive health information and services even harder.